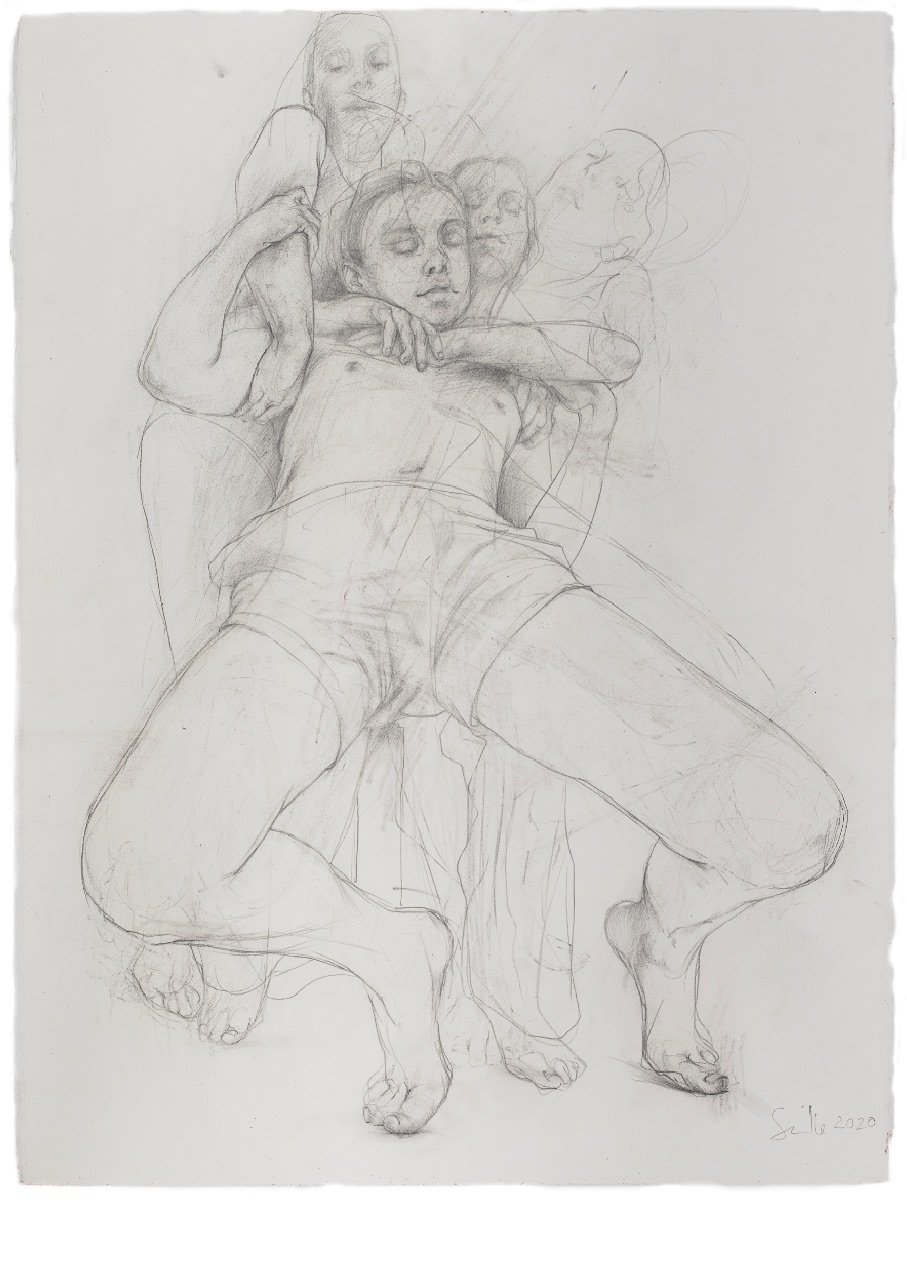

Jenny Saville

Jenny Saville

Pietà Study I, 2020

Unframed: 30 3/16 x 22 11/16 in. (76.7 x 57.6 cm)

Framed: 35 x 27 1/2 x 1 3/4 in. (89 x 70 x 4.5 cm)

This work is unique

Provenance: Courtesy of the Artist and Gagosian Gallery

Human perception of the body is so acute and knowledgeable that the smallest hint of a body can trigger recognition.

—Jenny Saville

In her depictions of the human form, Jenny Saville transcends the boundaries of both classical figuration and modern abstraction. Oil paint, applied in heavy layers, becomes as visceral as flesh itself, each painted mark maintaining a supple, mobile life of its own. As Saville pushes, smears, and scrapes the pigment over her large-scale canvases, the distinctions between living, breathing bodies and their painted representations begin to collapse.

Born in 1970 in Cambridge, England, Saville attended the Glasgow School of Art from 1988 to 1992, spending a term at the University of Cincinnati in 1991. Her studies focused her interest in “imperfections” of flesh, with all of its societal implications and taboos. Saville had been captivated with these details since she was a child; she has spoken of seeing the work of Titian and Tintoretto on trips with her uncle, and of observing the way that her piano teacher’s two breasts—squished together in her shirt—became one large mass. While on a fellowship in Connecticut in 1994, Saville was able to observe a New York City plastic surgeon at work. Studying the reconstruction of human flesh was formative in her perception of the body—its resilience, as well as its fragility. Her time with the surgeon fueled her examination into the seemingly infinite ways that flesh is transformed and disfigured. She explored medical pathologies; viewed cadavers in the morgue; examined animals and meat; studied classical and Renaissance sculpture; and observed intertwined couples, mothers with their children, individuals whose bodies challenge gender dichotomies, and more.

A member of the Young British Artists (YBAs), the loose group of painters and sculptors who came to prominence in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Saville reinvigorated contemporary figurative painting by challenging the limits of the genre and raising questions about society’s perception of the body and its potential. Though forward-looking, her work reveals a deep awareness, both intellectual and sensory, of how the body has been represented over time and across cultures—from antique and Hindu sculpture, to Renaissance drawing and painting, to the work of modern artists such as Henri Matisse, Willem de Kooning, and Pablo Picasso. In the striking faces, jumbled limbs, and tumbling folds of her paintings, one may perceive echoes of Titian’s Venus of Urbino (c. 1532), Rubens’s Christ in the Descent from the Cross (1612–14), Manet’s Olympia (1863), and faces and bodies culled from magazines and tabloid newspapers. Saville’s paintings refuse to fit smoothly into an historical arc; instead, each body comes forward, autonomous, voluminous, and always refusing to hide.