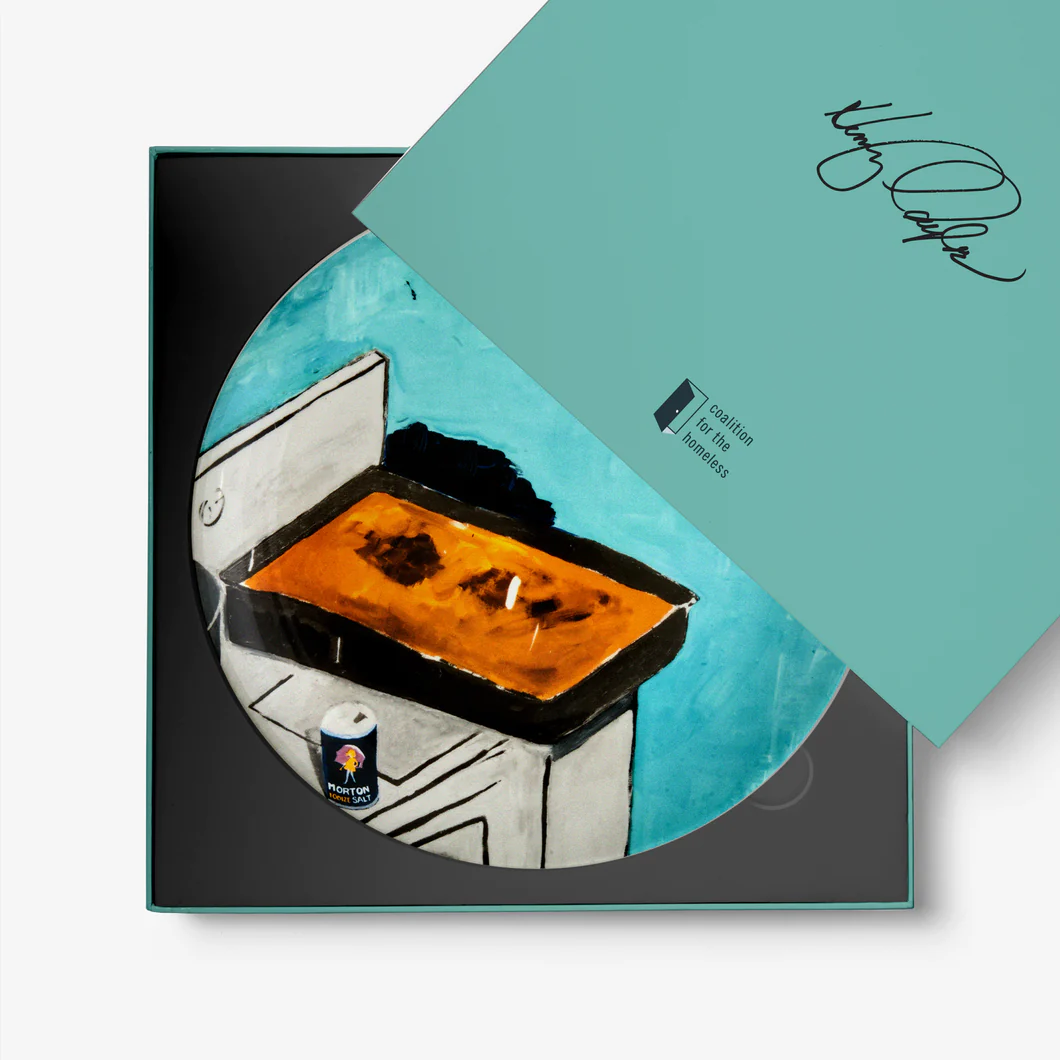

Henry Taylor

Winning Bid: $3,000.00

Henry Taylor

Cora, (cornbread), 2008 (© Henry Taylor Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth; Supported by Hauser & Wirth)

Fine bone china with custom box; Dishwasher and microwave safe

Printed signature and edition details on verso

10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm) diameter

This work is from an edition of 250

Produced by Prospect for Artware Editions

Provenance:

Artware Editions

Private collection, New York

Estimate:$3,000-4,000

Item condition: New

Henry Taylor’s imprint on the American cultural landscape comes from his disruption of tradition. While people figure prominently in Taylor’s work, he rejects the label of portraitist. Taylor’s chosen subjects are only one piece of the larger cultural narrative that they represent: his paintings reveal the forces at play, both individualistic and societal, that come to bear on his subject. The end result is not a mere idealized image, but a complete narrative of a person and his history. Taylor explains this pursuit of representational truth: ‘It’s about respect, because I respect these people. It’s a two-dimensional surface, but they are really three-dimensional beings.’[1]

Taylor is voracious and eclectic in his sourcing of subjects. This ‘hunting and gathering,’[2] as he defines it in his own words, is above all, an active process—one in which Taylor often mines his own history and experiences. In his studio, newspaper clippings and historical photographs of civil rights figures sit alongside his own snapshots of people both strange and familiar to him. This library of images, in turn, is surrounded by a collection of disparate objects that Taylor amasses from estate sales, his travels abroad, and local flea markets. Scattered across the studio spaces are infinite piles of historical tomes and artist’s monographs. All of these objects and visual documents eventually feature both in his paintings and as building blocks for totemic sculpture. But Taylor’s choice of painterly subject—from memory and archival materials, to the live sitter—is firmly dependent upon his sense of connection driven by empathy. His sumptuous depictions, painted rapidly and loosely, capture his subject’s nuances and mood with gestures and passages of flat, saturated acrylic color offset by areas of rich and intricate detail. The intensity with which he paints is reflected by his brushwork: a network of kinetic strokes that seek to capture a feeling before it flees. Taylor’s subjects, which range from members of the black community to symbolic objects representative of historical struggle, span the breadth of the human condition; each work is a holistic visual biography and permanent record of a person or people’s history.

Born in 1958 in Ventura, California, the youngest of eight children, Taylor’s initial exposure to the medium of painting came from his father, who was a commercial painter employed by the U.S. Government at a naval air station. In junior high school, Taylor began to vigorously absorb the tenets of major art historical movements spanning the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries. Taylor later studied at Oxnard College, where he studied Journalism, Anthropology, and Set Design, and made the acquaintance of James Jarvaise, the Head of the Department of Fine and Performing Arts. Jervaise was instrumental in instilling the young painter with a sense of vocational efficacy that helped to focus Taylor’s efforts entirely on his artistic practice. Taylor’s formal training came in the 1990s when he studied at The California Institute of the Arts while also working as a psychiatric technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital. It is here where Taylor developed his guiding sense of human connection while creating portraits of his patients. His practice evolved to exceed the boundaries of canvas: he began to paint the surfaces of found and discarded domestic objects like furniture, cereal boxes, empty cleaning bottles, and even packs of cigarettes. From these, Taylor creates assemblage sculptures, stacking and affixing disparate objects together to create, in some instances, faux African tribal masks from inverted Clorox bleach bottles erected on broomsticks.

What unifies Taylor’s practice across two and three dimensions is that it supersedes the confines of any traditional genre of painting and sculpture. His four-decade long practice combines pillars of figurative, landscape and history painting. Each result is a complete narrative that reflects the breadth and depth of his subject.

Taylor lives and works in Los Angeles. He has been the subject of numerous exhibitions in the United States and internationally, and his work is in prominent public collections including the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, France, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx NY, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburg PA, The Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles CA, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston MA, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles CA, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles CA, Museum of Fine Art, Houston TX, Museum of Modern Art, New York NY, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham NC, Pérez Art Museum, Miami FL, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco CA, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York NY, and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY.

In 2018, Taylor was the recipient of The Robert De Niro, Sr. Prize in 2018 for his outstanding achievements in painting. Taylor’s work was presented at the Whitney Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY in 2017 and 58th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy in 2019.

[1] Sargent, Antwaun, ‘Examining Henry Taylor’s Groundbreaking Paintings of the Black Experience’, on: artsy.com, 16 July 2018

[2] Smith, Zadie, ‘Henry Taylor’s Promiscuous Painting’, on: newyorker.com, 23 July 2018

(Taken from HauserWirth.com)

Auction History

Auction has finished

Highest bidder was: VU

| Date | Bid | User | Auto |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 8, 2023 8:01 am | $3,000.00 | VU | |

| November 8, 2023 8:01 am | Auction started | ||